A History, 1880-1980

by William Lee Younger

Drawings

by Lucy Durand Sikes

This essay appeared first in the Society’s Centennial Handbook. Photographs included here supplement that text.

The Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia created for Americans anew awareness of their past and confidence in the future. Here they saw not only the technical achievements of the world, but many for the first time also saw historic American documents and notable examples of art and architecture from their seventeenth and eighteenth century past. As a result of this exposure and concurrent books and articles on early America, there emerged in the last quarter of the nineteenth century many well-known patriotic and historical societies. The New England Society in the City of Brooklyn, incorporated in 1880, was one of these.

It is an organization which emerged during the nineteenth century in an era of rapid social mobility and abrupt, profound change. These factors, Charles Dellheim suggests in The Face of the Past, made the sense of the past “particularly valuable as a source of orientation for those living an unprecedented life in an open-ended world.” The same holds true today when a sense of the past provides stability and direction in the contemporary world. The history of the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn reflects the myriad permutations in America during the past century and particularly in Brooklyn. Its fortunes have ebbed and flowed. Its emphasis has changed. Above all, it has endured and today attracts men of the same caliber and spirit as before.

Part I – Foundations

One might ask a century later, “But why a New England Society in Brooklyn?” Census records of the 1870s indicate that there were more people of New England descent living in Brooklyn, already the nation’s third largest city, than in Boston. As a major manufacturing center and with a seaport larger than New York’s, it attracted great numbers of New Englanders in the years immediately preceding and after the Civil War.

In spite of its bustling waterfront, shipyards, factories, and breweries, Brooklyn’s character remained essentially residential, a quality highly regarded and perpetuated by its New England population. Mayor Seth Low appealed to this sentiment in his response to the toast “The City of Brooklyn” at the New England Society’s Fourth Annual Festival in 1883 when he said, “I want you to think of this city, not as a place of residence, not simply as a collection of houses in which you dwell and from which you go to your work across the river or within your own limits; but as home. What do men do for their homes? They beautify them; they make them attractive; they are the places about which their affections cluster, and men will die for their homes when they will turn the coward shoulder to almost any other cause.”

And so it was with a strong spirit of community that a group of seven influential Brooklyn men came together in February of 1880 to form the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn. Before notary John Heydinger, Jr., they appeared on the twenty-sixth of that month and formally stated their desire to form a society whose objectives would be “to encourage the study of New England history and for such purpose to establish a library, and also for social purposes, and to promote charity and good fellowship among its members.” The following day, February 27, 1880, their certificate of incorporation was approved and rued in both the office of the Clerk of Kings County and that of the secretary of state in Albany.

A. Antecedents

This New England Society of 1880 was the successor to an earlier Brooklyn society of the same name which was never incorporated and was presumably defunct by the time the present group was organized. Formed in 1847 with similar objectives, it had attained a membership of 156 in 1848.

Scant evidence of this “parent” organization remains in the archives of the Society, and it is rarely referred to in the Annual Reports. One notable exception appears in the Nineteenth Annual Report of 1899: a reproduction of the Bill of Fare from the “Second Forefathers’ Day Anniversary Dinner of the New England Society of Brooklyn, December 22, 1848.” This reproduction was featured prominently in the program for the Annual Dinner of 1898, at which Governor elect Theodore Roosevelt was the guest of honor and whom the Brooklyn New England Society no doubt wished to impress with its venerability.

The Society also owns two copies of the Constitution and By-Laws of the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn, dated 1847 and 1848, the latter containing a list of members. The earlier copy was presented to the Long Island Historical Society in 1863 by Alden J. Spooner, a member of the 1847 Society and first Historiographer of its 1880 successor. Among the founders of the present Society, its first officers, councilors, and directors, Spooner appears to be the sole link with the earlier group, and yet it is not mentioned in his detailed obituary in the Annual Report of 1881.

Benjamin D. Silliman, first President of the 1880 Society, vaguely spoke of the previous organization at the first Annual Meeting in the Assembly Room of the original Academy of Music on Montague Street on December 7, 1880, but his references concerned only problems of incorporation prior to 1875. However, in that year a general law was passed by the state legislature for, as Silliman said, “the formation of societies for certain purposes including such as this.” But another five years were to pass before the “Founding Fathers” took legal steps to establish officially their hitherto somewhat informal group. Their treasury in 1880, a rather hefty $3,474.82, makes one wonder if this was a legacy from the Brooklyn New Englanders of 1847.

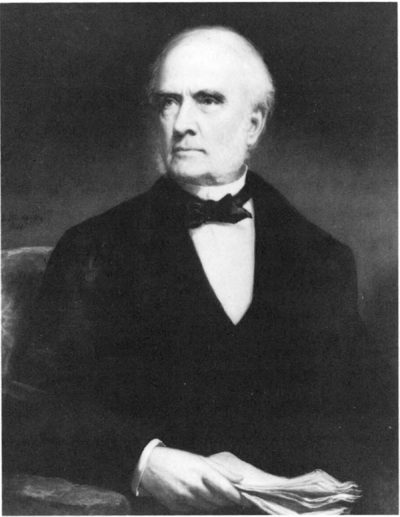

BENJAMIN D. SILLIMAN. This portrait of the first President of the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn was painted by Daniel Huntington in 1880, the year the Society was founded and when Silliman was seventy-five. Huntington, a New York artist, was a contemporary of Silliman’s and like him witnessed nearly a century of American history. The portrait has been in the collection of the Long Island Historical Society since 1890.

The seven incorporators, sharers of a New England heritage – Benjamin D. Silliman, Calvin Edward Pratt, Ripley Ropes, John Winslow, Hiram W. Hunt, Charles Storrs, and William Burrage Kendall – were men prominent in the civic, professional, commercial, religious, and social activities of Brooklyn. In spite of Brooklyn’s size the society in which they moved, concentrated in Brooklyn Heights and “the Hill” (Fort Greene and Clinton Hill), was comparatively small, and they were closely acquainted with one another professionally and socially. For years they had met frequently at the Club or around the Directors’ table at the Long Island Historical Society. Together they watched the leading performers of the day at the Academy of Music and viewed paintings in the adjoining galleries of the Brooklyn Art Association. Consequently, these institutions have had a long association with the New England Society from its inception.

The first quarter century of the Society’s existence is stamped indelibly with the influence and character of its first President, Benjamin D. Silliman, also a founder of the Long Island Historical Society. Silliman, born in 1805 in Newport, Rhode Island, was the grandson of General Gold S. Silliman, a Revolutionary War officer who fought in the Battle of Long Island in 1776. Though he resided in Brooklyn from 1823, he practiced law in New York and had vivid memories of personal associations with Aaron Burr. Silliman, who lived on unti11901, was a visible link between the formative years of the nation and the industrialized early twentieth century. Silliman’s earnest dedication to the ideals set forth by his ancestors, who also included the much romanticized John Alden and Priscilla Mullens, is apparent in these words from one of his first addresses to the infant Society in 1880. “Each of us has inherited from our Pilgrim ancestors the duty of vigilantly protecting, extending, and perpetuating, each by his voice, his vote, and his life if need be, the religious, political, and personal freedom which they bequeathed to us.”

B. December 21

Foremost among the by-laws of the Society was Article III which called for an Annual Festival (also popularly known as the New England or Forefathers’ Day Dinner) to be held just before Christmas to commemorate the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth in 1620, and it was with this banquet, the first of many, that the Society caught national attention on December 21, 1880. Elaborate preparations had begun early in the new year. The site chosen, which was to remain popular for some fifteen years, was the Assembly Room of the Academy of Music and its adjoining Art Gallery on Montague Street between Court and Clinton, then the center of Brooklyn’s growing commercial and financial district. The Academy offered size, prestige, and convenience. Already the long-awaited opening of the Brooklyn Bridge was drawing business away from lower Fulton Street.

In selecting the date of December 21 for the Festival, as opposed to December 22 – the day on which the 1847 Society had honored the Pilgrim forefathers – the new Society followed a precedent set in 1850 by the Pilgrim Society in Plymouth. To substantiate the date, the Directors asked Professor Charles E. West to read a paper, prepared at their invitation, to the general membership which explained (and obviously convinced them) that the twenty-first was the “true anniversary day of the Landing of the Pilgrims.” In essence his conclusion was based on a systematic conversion of December 11, the day of the landing on the Julian calendar (in use in 1620), to its equivalent on the Gregorian calendar, which superseded the Julian and was adopted in the American colonies in 1752.

Characteristic decoration of the Assembly Room included large coats-of-arms of the thirteen original colonies which hung on the walls together with the flags of the United States and Brooklyn. Potted palms were placed in strategic places about the hall, and elaborate floral arrangements adorned the tables which were often further embellished with confections in the shapes of churches, schoolhouses, mills, tunnels, and railroads – “symbols of power, progress, and prosperity of New England.”

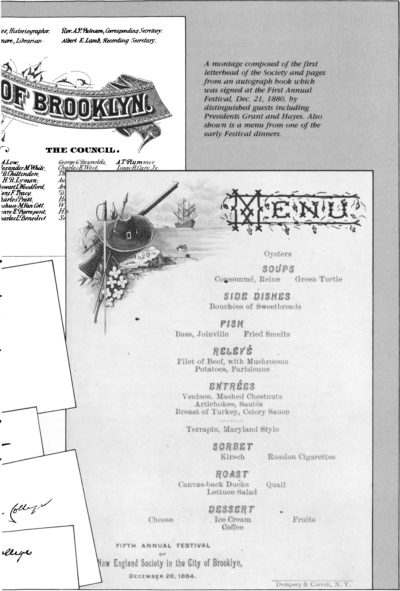

The “hospitable board” – adequate beyond belief, as illustrated by a typical menu of the period – was furnished until 1890 by Delmonico’s of New York. In its first report, the Festival Committee deemed the fare “excellent” and the service “admirable.” The only error the Committee seems to have made in planning its initial festival was miscalculating the length of time it would take the assemblage to move through the many courses. The dinner hour, following a reception in the Art Gallery, was set for 7:00p.m., but when the toasts and after-dinner addresses finally began three invited guests were unable to speak because of the late hour. Some egos were bruised, and thereafter, as long as the event continued on such an elaborate scale, dinner began at six o’clock. However, as late as 1896, speakers still requested “not to be put too far down on the list.”

The reputation of Brooklyn’s Annual Festival had spread as far south as New Orleans in 1886, when E. K. Converse, a commission merchant of that city, wrote to John Winslow, the Society’s second President, about a dinner organized by the New Englanders of New Orleans at which there were “several fresh, live Yankees attending the North, Central, and South American Exposition, seventy ladies, and one-hundred-thirty gentlemen present for a royal jolly time.” However, their “baked beans, brown bread, and tea from an old kettle brought over with the Pilgrims on the Mayflower” stand in Spartan contrast beside the magnificence of Delmonico’s.

Until the mid-1890s, the Annual Festival in Brooklyn, inclement weather notwithstanding, attracted an average of 300 members and their male guests. Tickets were greatly sought after, and seating arrangements were given the utmost attention. To add to the splendor and dignity of the occasion during this period, each member wore a satin badge (usually furnished by Dempsey & Carroll, then on Fourteenth Street, New York) bearing the Society’s seal and the Festival date stamped in gilt across it.

In 1888 Harold J. Goodwin of the New England Society in Philadelphia requested an impression of the Brooklyn Society’s seal and added, “Our Philadelphia Society had never aspired to such a luxury till within a month or two, and we are looking around for designs and suggestions.”

THE PRESIDENT’S MEDAL, or “Official Badge,” originally had a blue ribbon. It arrived in Brooklyn just in time to be worn by Benjamin Silliman at the first Festival in 1880, and since then has been worn by presidents of the Society at official functions.

In 1880 a medal featuring the Society’s seal was designed by Tiffany & Company and executed in gold and enamel. A somewhat frantic correspondence on the eve of the first Festival between John Winslow and J. H. Whitehouse of Tiffany suggests some problem about finishing the case for the medal. However, in the darkness of late afternoon on December 20, the “Official Badge,” with a blue ribbon attached, had been fitted into its case and was on its way by ferry across the East River by special messenger.

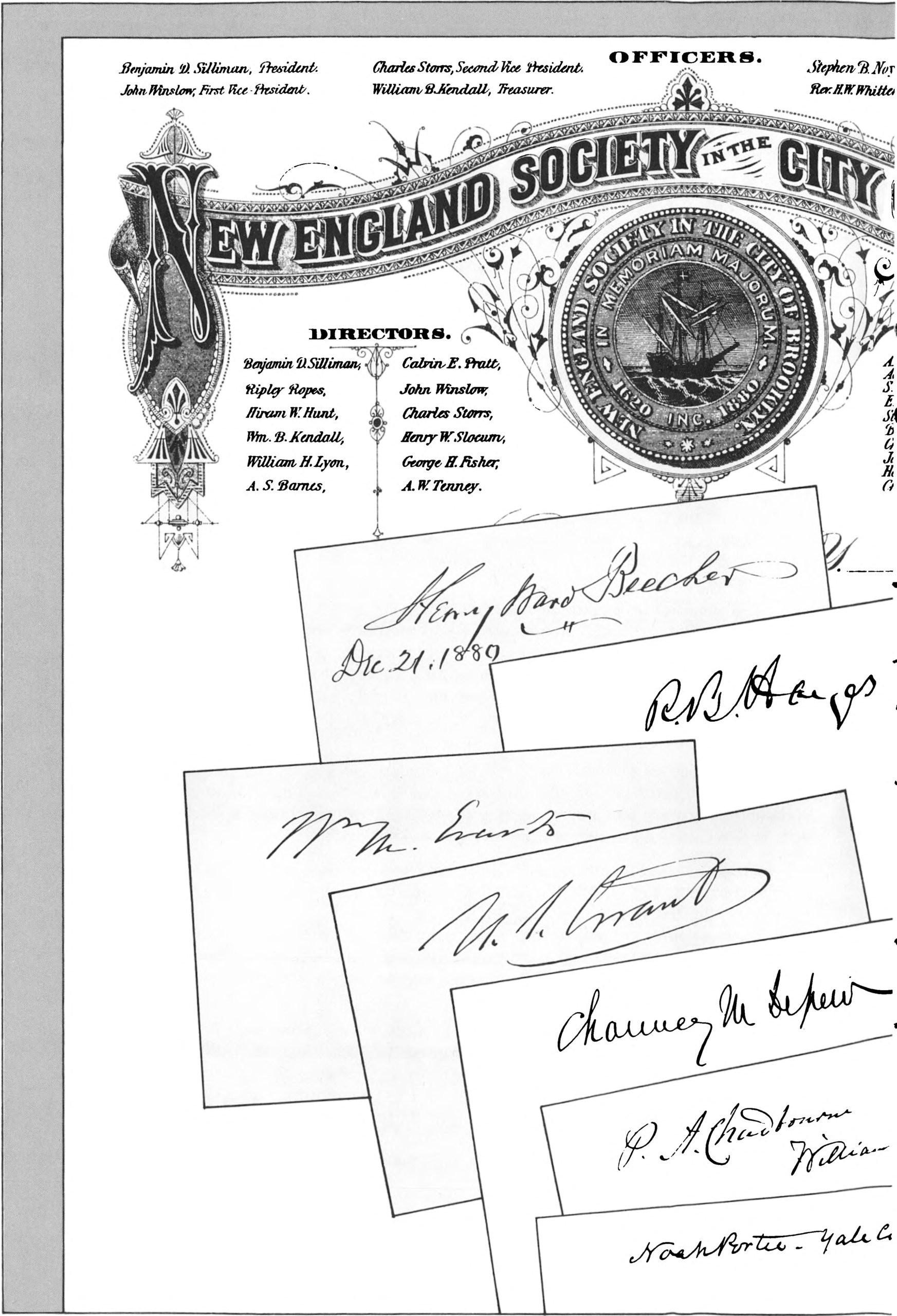

This medal, always the proud possession of the Society, hung from Benjamin Silliman’s neck as he received the honored guests on December 21, 1880, and a distinguished group it was. Rutherford B. Hayes, President of the United States, headed the list which included General Ulysses S. Grant, former President and Civil War hero; Secretary of State William M. Evarts; General William T. Sherman; the Presidents of Yale and Williams – Noah Porter and P.A. Chadbourne; Henry Ward Beecher; Chauncey M. Depew – soon to become President of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad and perennial after-dinner speaker; and Edward Everett Hale, best remembered today for his tale of patriotism The Man Without a Country. Their autographs, gathered on that evening, are preserved in a book in the Society’s archives. Particular attention was also given to those guests representing the Society’s sister organizations, namely the New England Society in the City of New York, the St. Nicholas Society, and the St. Patrick Society.

Of the guests at the head table, Sherman especially endeared himself to the Society. He was made an honorary member and continued to come to the Festival until his death in 1891, traveling by carriage from his residence in New York at the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Sherman had first come to Brooklyn in the summer of 1836 to visit his uncle Charles Hoyt, who lived at the foot of Remsen Street, and had often returned during his boyhood. Ruminating upon the years, he said to his Brooklyn audience, “. . . when I come back to you in my old age and visit you, I come back to the friends of my youth.” They loved it.

The first Festival with its eminent guests, elaborate dinner, toasts, and subsequent speeches established a pattern which was to continue until the First World War. Faces and locations changed; menus and ceremonies were simplified; but the basic form and tenor remained. Though the number of speeches and the time allotted for them declined between 1880 and 1914, these addresses, representing the intellectualism and abiding influence of New England, continued to be at the heart of every Festival. They were recorded meticulously by a stenographer, often the official stenographer of the Brooklyn Supreme Court, then printed annually with other Society proceedings and bound for distribution to the membership and to leading libraries. This practice continued until about 1913.

For over thirty years the press, usually representing no less than ten Brooklyn and New York newspapers, had its own table at the Annual Festival. Their reporting of the Society’s activities attracted readers both locally and in cities as far away as St. Louis.

In this connection, one rather poignant incident occurred in the spring of 1885 when one Thomas Coles, a mechanic, who apparently was suffering from a mental disorder, read in the St. Louis Post Dispatch an account of the Rev. John W. Chadwick’s address to the New England Society on witchcraft. Convinced that he was bewitched and obviously in a state of torment, Coles wrote to President John Winslow requesting a book on “whitchcraft and its teaching” and asking him “what corse to persue” now that medical help had failed him.

If Winslow replied it is not recorded (and one can theorize that he did not), but he did send Coles’s letter on to Chadwick, minister of the Second Unitarian Church, then at Clinton and Congress Streets. Chadwick returned it and wrote, “I return the pitiful and yet amusing letter. No laughing matter I fancy to the poor devil who wrote it.”

Until it was suspended about 1912, one of the most important and demanding offices of the Society was that of Historiographer, whose principal job it was to write the obituaries of deceased members. These detailed necrologies were included in the Annual Reports and are today of great value to the student of nineteenth and early twentieth century Brooklyn history and to the genealogist. Between 1880 and 1912 this position was held by only seven men, the most celebrated of whom was Paul Leicester Ford. The son of bibliophile Gordon L. Ford, whose collection of American books and manuscripts is outstanding, this brilliant man suffered from what was probably dwarfism. This condition, combined with generally poor health, led to his being educated at home on Clark Street in his father’s library. Later he distinguished himself as an editor, bibliographer, historian, and novelist. His murder in 1902, at the hand of his brother Malcolm, a noted amateur athlete, created a sensation at the time.

In 1884, with Silliman as President, the Society attained its largest membership, 425; but the seventy-nine-year-old “Grand Old Man” of the New York and Brooklyn bars, declined reelection in 1886 and stepped down in favor of his close friend and protégé, John Winslow, a Boston-born, Harvard-educated lawyer who was admitted to the Kings County Bar in 1853. Though Winslow’s administration lasted only four years, he continued to wield significant influence as a member of the Invitations Committee which selected speakers and prepared and assigned toasts at the Festival. Winslow’s correspondence is rich with material about the Society, and he obviously worked tirelessly for its well-being.

C. Relics

It was also in 1884 that William T. Davis of the Pilgrim Society presented to the New England Society a number of “relics” from which he thought a gavel could be made: for the head – a block of wood from Scrooby in Nottinghamshire, England, birthplace of Plymouth Colony’s spiritual leader, William Brewster; for the handle – a smaller piece of wood from the Hancock house in Boston; for embellishment – the ivory handle of a cane and a fragment of Plymouth Rock which, Davis instructed Winslow, “You can insert in an appropriate place.”

The gavel was handsomely constructed according to Davis’s suggestions, and an engraved band of silver around its handle proclaims its components’ various origins. As for the piece of Plymouth Rock, it was mounted on a low rectangular pedestal with inclined sides, each of which bears a silver panel. These display engraved motifs and contemporary inscriptions. A proud possession of the Society, the gavel was used by successive Presidents for many years, and the rock, on its silver-embellished plateau, was a prominent feature on the speaker’s table at New England Society dinners.

But by 1953 these important mementos had disappeared, and Charles Lauriston Livingston, Jr., active in the Society at that period, was making a vain attempt to locate them. They finally surfaced by chance in April 198O, discovered in the former law office of Hunter L. Delatour, President of the Society in 1935, where they had lain almost forgotten for over a quarter of a century.

The Pilgrim Society made a concerted effort in the mid-1880s to establish close ties with the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn and in 1886 solicited its aid to complete the Monument to the Pilgrims begun in 1859 atop one of the highest hills in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Although the New England Society had formed a committee of its own in 1883 to plan the erection of a monument in Brooklyn “in commemoration of the martial deeds of Brooklyn’s sons” (a scheme which never came to fruition), the national character of the Plymouth monument in a strongly patriotic age had great appeal. The Society sent a donation toward finishing the monument and was well represented by ten of its members at the dedication at Plymouth in 1889.

D. Innovations

With the advent of John Winslow’s presidency, the Society sought to expand its activities and toward that goal in the new year of 1886 the Directors adopted a resolution to hold an Annual Reception between February and May, with speakers and refreshments, to which ladies could be invited. Though the Annual Festival remained a stag affair until 1896, ladies were present at the Second Annual Meeting in 1881 in the lecture room of the Long Island Historical Society, an auditorium popularly known as “Historical Hall.” In addition, ladies were always included in what were referred to as Semi-social Meetings which began in the early 1880s. These evening “family affairs,” usually held at the Brooklyn Art Association, No. 174 Montague Street, featured two short addresses, music, a collation, and dancing. Indeed, in 1907 there was even a proposal to admit ladies to membership.

It was at the Annual Reception in February 1887 that Kate Field became the first woman to address the Society, a precedent followed at the One Hundredth Annual Meeting in 1980 when Dianne H. Pilgrim, Curator of Decorative Arts at the Brooklyn Museum, spoke at the Brooklyn Club on “The American Renaissance,” the cultural period during which the Society was incorporated.

Kate Field, a much publicized intellectual of the time, was popular on the lecture circuit and known as “an apostle of reforms.” From The Arlington in Washington, D.C., where she had spoken on Mormonism, she accepted, in a letter fraught with questions, John Winslow’s invitation to appear in Brooklyn. She wrote, “Now please let me know what sort of an occasion it is, how people dress, who delivers the address, when the carriage should be ordered in New York, when ordered to return for me, and whether I can bring a friend.”

Advising her to depart New York no later than 7: 15 p.m. but leaving the matter of the return trip unanswered in his reply to her, Winslow concentrated primarily on attire for the evening. “As to how people dress,” he said, “well, they dress pretty well. I have not the knowledge of how to describe the dress the ladies wear except to say the effect (to me) is good. Some of the gentlemen appear in evening dress; some do not.” He closed with a reassuring, “You may bring as many friends as you like.”

Another person to leave his mark upon the Society was its Treasurer from 1887 until 1891, the urbane, jocular Charles N. Manchester. In the paint and oil business and an early member of the Montauk Club, Manchester was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Civil War. His letters, usually written from No. 291 DeKalb Avenue, his tall corner brownstone at Waverly Avenue, sparkle with wit and sophistication.

He delighted in collecting delinquent dues from members who could well afford to pay, and on such occasions he often dashed off a note to the Secretary confirming his receipt of the money in question. His correspondence with Thomas S. Moore on March 6, 1890, is typical. In it he noted receiving Mr. Worthington C. Ford’s check – Worthington C. Ford was the brother of Paul L. Ford and also a successful writer – which he had credited to his account with “ghoulish glee.” He added, “I am glad that the act of having robbed the gentleman to this extent does not rest on my conscience.” The note closed with a jestful, “Yours in crime.”

E. Losses

In another note to Moore during his treasurer ship, Manchester gently chided the Secretary for the deficiencies of his membership roster. “I will take the earliest opportunity to return your roll book which I regret to say is not complete enough for my purpose. The dead have not been removed nor the living added.” It was a great loss to the Society when Colonel Manchester, who would probably have become its President, died suddenly on February 16, 1892, in the waiting room of the Brooklyn station of the Brooklyn Bridge.

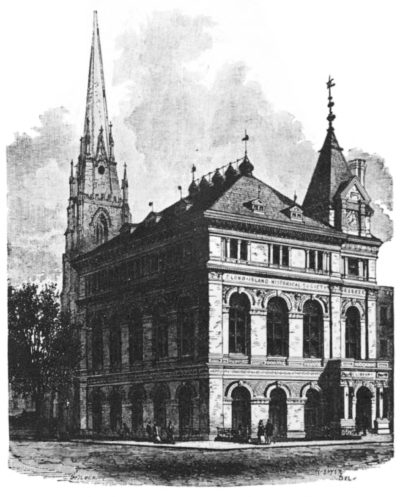

THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Located at Pierrepont and Clinton Streets, the Society’s building, designed by George B. Post, was begun in 1878 and completed in 1880. John Winslow was an organizer of the Long Island Historical Society and chairman of the committee which selected its motto, “History, the Witness of Time.” For this eclectic style building Olvin Levi Warner, a noted sculptor, was employed to execute certain terra cotta ornaments, making Post one of the first architects in America to use architectural terra cotta. Though a clock dial is prominent on the north front, a clock was never installed, and a writer in Brooklyn Life in 1892 lamented the fact. “There should be a public timepiece there, if nothing more than to attract the attention of indifferent people to the beautiful facade of the building.” (From the collection of the Long Island Historical Society)

The 1890s brought changes to the New England Society and to Brooklyn. Though the population of the city continued to grow and though President Steward L. Woodford in 1896 could still speak of Brooklyn as “peculiarly a New England city,” membership began to decrease as did attendance at the still brilliant Festivals. In 1895, at the Sixteenth Annual Meeting, formal notice was made of this phenomenon with a sad comment upon the “many deaths” and the fact that “our young New England men are not coming into the Society with the old enthusiasm.” A generation was passing from the scene, and Brooklyn’s future identity was uncertain as consolidation with New York was contemplated.

As early as 1891 member Daniel S. Moulton had been authorized by the Society to solicit persons of New England descent to become members. For this service he was paid $100 per annum and received 20 percent of the initiation fees and dues of his “recruits.” The Rev. William H. Ingersoll, Librarian from 1893 to 1909, took over this duty in the first year of his office.

The Society’s solicitation in the spring of 1891 of Colonel Loomis L. Langdon, Commandant at Fort Hamilton, illustrates the strong effort to attract new, influential members who were active in Brooklyn affairs. Langdon, married to Harriet Creamer, daughter of William G. Creamer – a New England Society member since 1880 – found himself in a somewhat awkward position and first declined membership, explaining that as “Commandant of military forces of the government on Long Island, it seems hardly suitable for me to join an organization so distinctively Republican as the New England Society.” But General Alfred C. Barnes, who sponsored Colonel Langdon, convinced him that his impression was incorrect.

Satisfied, Langdon wrote a note in May 1891 accepting his election and stating he “was pleased by learning that so many of my Democratic friends belong to the Society.” To this note Barnes appended in his distinctive, flowing hand the comment, “I think we corralled him skillfully.”

In 1893-1894 a committee composed of J.W. Gilbert, Frederic A. Ward, and John Winslow undertook to secure by subscription a marble bust of Benjamin D. Silliman, then in his late eighties but still active as a Director and revered by the membership. Noah Davis, responding in January 1894 to the ad hoc committee’s appeal for funds, expressed this sentiment aptly when he wrote of Silliman, paraphrasing in part the words of Connecticut-born poet Fitz-Greene Halleck (1790- 1867), “I hope your committee will do something worthy of the noble gentleman of whom it can be truly said – None know him but to love! None name him but to praise!”

THIS ALEXANDER HAMILTON STATUE once looked north across Remsen Street at the corner of Clinton Street in front of the Hamilton Club. Completed in 1892 by Brooklyn sculptor William Ordway Partridge, it was displayed at the Columbian Exposition before it came to Brooklyn Heights. The club was a victim of the Depression, and its building was demolished in 1936. The statue was given to the Hamilton Grange in Manhattan and now looks west across Convent Avenue at 141st Street.

The committee gave the $1,000 commission for the bust to William Ordway Partridge (1861-1930), Paris-born, Brooklyn-bred sculptor, whose statue of Alexander Hamilton stood in front of the Hamilton Club at Remsen and Clinton Streets in 1893 and was well known to them.

In late January 1894 Partridge began the bust which he proposed to be “like his bust of Dr. Hale [probably Edward Everett Hale] at the Hamilton Club – heroic, large, life size.” Work continued without a snag until September 1894 when Partridge wrote from his studio in Milton, Massachusetts, informing the committee he had been ill with “malarial fever” and the plaster cast he had sent to Paris, where it was to be executed in Italian statuary marble, was broken in transit. He asked for $100 on account as he was unable to pay his workmen.

After numerous delays and last minute reassurances from Partridge – hastily penned from the Reform Club in New York on the eve of the dedication – the bust was unveiled on May 8, 1895, at the Brooklyn Art Association and soon after delivered to the Long Island Historical Society which Silliman had helped to found and which the New England Society had always looked upon as the eventual repository for its still unrealized New England collection.

Though the bust was highly acclaimed, especially by the well-known American artist William Merritt Chase, the committee rejected the pedestal, and Winslow wrote to Partridge on May 13, 1895, expressing his disapprobation. “I don’t like that miserable, dingy (temporary I trust) standard the bust rests upon in the Historical Rooms. Please move in this matter at your earliest convenience as I have been expecting you to do.” How the beleaguered Partridge, who claimed that his profit was lost by this time, responded is not known.

In 1894 the Society joined with the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and the Long Island Historical Society in sponsoring and sharing in the expense of a lecture series illustrated by “lantern photographs.” No doubt this series grew out of the appeal of such lectures at the New England Society’s Annual Meetings. The lecture program was popular for many years and drew large audiences of several hundred throughout the season.

Because women from the outset had participated in most of the Society’s social events, it was not a radical departure when, in 1896, they were invited to attend the Annual Festival. Perhaps it was their anticipated presence which prompted the Invitations Committee in its attempt, though unsuccessful, to engage Julia Ward Howe as a speaker for the occasion.

F. The Pouch

However, the site chosen for the 1896 Festival is significant. After fifteen years at the Academy of Music, it was moved to the smaller but very stylish Pouch Gallery in the Hill section of Brooklyn. This move marks the emerging preeminence of the Hill in Brooklyn social life.

THE POUCH GALLERY. This great brownstone mansion with a frontage of eighty-six feet on Clinton Avenue at Lafayette Avenue was designed about 1885 by Brooklyn architect William A. Mundell in the neo-Grec style. This style came to America via France but found greater popularity on this side of the Atlantic than in Europe. In the late 1880s Alfred J. Pouch, Standard Oil Company executive, opened the house as a fashionable catering establishment, a use in which it continued for about half a century. In 1896 the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn held its Annual Festival here, and the Pouch Gallery remained popular with the Society for many of its social activities until 1908.

The Pouch Gallery, or “The Pouch” as it was affectionately called, stood until its demolition in the 1930s at the comer of Clinton and Lafayette Avenues. Built in the late 1880s as an impressive residence for Robert Graves, who died before its completion, the mansion was purchased by Alfred J. Pouch, an enterprising businessman and a member of the original Standard Oil Company. Pouch finished the house and at the same time altered it for “public events of a fashionable nature,” a use which it enjoyed for many years. Except for a return to the Art Association in 1900, the Pouch Gallery was the preferred location for the Society’s dinners and receptions until the new Academy of Music was erected in 1908.

Throughout the 1890s the Society continued to attract luminaries to its events. Former President Grover Cleveland headed the list of honored guests at the Annual Festival in 1891. The Festival the following year was one of the last public appearances of the eminent Episcopal Bishop, Phillips Brooks, Rector of Trinity Church, Boston, who died January 23, 1893. In the Society’s archives are letters, written on black-bordered mourning paper by the bishop’s brother Arthur, pertaining to the preparation for printing of his late brother’s speech delivered on Forefathers’ Day the preceding month.

Woodrow Wilson, then a forty-year-old professor at Princeton, spoke on Forefathers’ Day in 1896 to the toast “The Responsibility of Having Ancestors,” but the Invitations Committee regretted not having on the same evening an address by another noted educator, Booker T. Washington, who declined their invitation. In 1899 the presence at the Pouch Gallery of Thomas Nelson Page, Virginia novelist, who spoke on “The Debt Each Part of the Country Owes the Other” can be interpreted as a sign that Civil War wounds and sectional differences were healing as living memories of the conflict faded into the past.

As the century drew to a close the ninety-two-year-old Benjamin Silliman lived on in the big brick house on the northwest corner of Pierrepont and Clinton Streets, where his sisters Aurelia and Harriet acted as hostesses for their bachelor brother, and at his country place in Islip which he dubbed his “Box.” On March 10, 1897, in a wavering hand, he tendered his resignation as a Director of the New England Society offering as an excuse the fact he could no longer attend meetings. His resignation was promptly rejected, an action deeply appreciated by the old man for in essence it was a tribute. But feeling his isolation, he lamented, “Would that I could continue to enjoy the daily companionship of such friends – but the withdrawal of that great privilege is one of the grave and inevitable penalties of extreme old age.”

In 1898 he suffered yet another painful separation when seventy-three-year-old John Winslow, whom he idolized, died on October 18 at his home in Bay Ridge. The two men shared many interests. Over the years Winslow sought in vain to persuade his mentor to invest in apartment houses going up in the new sections of the city, but Silliman, who came to Brooklyn when it was still a village, steadfastly refused, saying, “I am unhappily too old-fashioned that I can hardly conceive that anything has abiding value east of Bond and Nevins, south of First Place, or north of Adams Street.” And Silliman, disapproving of Winslow’s atheistic leanings, was disappointed that the younger man would not “repent” and join the Reformed Dutch Church, though he himself was a Congregationalist.

G. Spirit of the Times

Caught up in the patriotic spirit engendered by the Spanish-American War (Rear Admiral George Dewey had accepted his election as an honorary member aboard his flagship in Manila Bay), the Society joined in two projects associated with the nation’s history. The first had actually begun in 1895, when the Society contributed toward the rebuilding of the First Church (or First Parish) at Plymouth which had been destroyed by fire. This was done in spite of the strong objections of some members who felt that the Society’s funds should be utilized for “something of a permanent character” in Brooklyn.

However, in 1902 there appears to have been widespread approval of the gift of two stained glass windows (commissioned from the Church Glass Decorating Company of Brooklyn) placed in the First Church and unveiled December 21, 1902. These windows, representing Civil and Religious Liberty in figures of Oliver Cromwell and John Milton, are in back of the pulpit and flank a window depicting the signing of the Mayflower Compact.

In a departure from tradition, there was no Forefathers’ Day Dinner in Brooklyn in 1902. Instead, it was held in Plymouth at Samoset House on the eve of the windows’ dedication. On this occasion an attempt was made to duplicate the menu of the first Forefathers’ Day Dinner given in 1769 by the Old Colony Club of Plymouth. In its second project the following year – 1903 – the Society gave money toward the raising of a suitable monument in Fort Greene Park to commemorate the 11,500 Revolutionary patriots who suffered and died in British prison ships anchored in nearby Wallabout Bay. Designed by Stanford White, the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument, a colossal Doric column crowned with a bronze brazier, was dedicated in 1908 by President-elect William Howard Taft before a crowd of 40,000 persons.

Built in the same year was Brooklyn’s new Academy of Music, replacing the former one destroyed by fire in 1903. It is not surprising that the New England Society, which had celebrated so many happy occasions on Montague Street, selected in 1909 the Academy’s new banquet facilities on Lafayette Avenue for both its Spring Meeting and Annual Festival. Though novel and spacious, the Academy’s Banquet Hall seems to have had serious drawbacks, and its popularity with the Society was brief. By 1914, and for many years thereafter, its choice was unquestionably the Hotel Bossert “On the Heights.”

Some of the objectionable features of the Academy were outlined in a letter from Jesse D. Crary, Managing Director of the New York Lumber Trade Journal, written in 1911 to the Society’s Secretary a few weeks before the Festival at which President William Howard Taft was scheduled to appear. Mr. Crary complained of the difficulty in hearing in the long narrow hall, the clatter of dishes, and the waiters’ muddy shoes which made the floor “about as bad as Broadway on a wet day.”

But some of his friendly criticism concerned the Dinner Committee’s apparent lack of regulation of the music. “The Star Spangled Banner,” wrote Crary, “was played just after the bird was served, and the consequence was that while we were all standing singing The Star Spangled Banner, the bird was getting cold. At my dinners (those for the New York Lumber Trade Association) I always have The Star Spangled Banner played with the sherbet.”

H. Writing History

On April 26, 1907, the Jamestown Exhibition, the tercentenary celebration of the establishment of the first permanent English settlement in America, opened in Virginia, and not to be completely overshadowed by the Virginians, the Brooklyn New Englanders, led by Adelphi College professor Charles Herbert Levermore, decided to demonstrate that Captain John Smith had devoted far more time and energy to developing New England than Virginia. Thus Dr. Levermore, who was also the Society’s Historiographer, proposed in April of 1907 that the Society publish a work on Smith’s contributions to New England colonization. The scheme met with enthusiastic approval; money for the project was appropriated; and work commenced in earnest.

Dedicated to the “present and future members of the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn,” the two-volume work, entitled Forerunners and Competitors of the Pilgrims and Puritans, was published in 1912 and is today in the collection of the Long Island Historical Society. In appreciation for his services and dedication in the preparation of this historical narrative, Dr. Levermore received an honorarium of $500 from the Society in 1914. Its scholarship notwithstanding, Forerunners and Competitors was not popular and numerous unsold sets remained in storage at the Long Island Safe Deposit Company for thirty-nine years until their disposal to book dealers in 1941.

Though never public knowledge, scandal touched the Society in 1910 when it was revealed that Herbert Owen, a trusted clerk in the office of the Society’s Treasurer, Franklin W. Hooper, had embezzled $930.50 from the Society’s funds. Hooper was a director of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Science and the first promoter of a great central library in the classic style as a companion structure to the Brooklyn Museum. Mortified, he paid this sum out of his own pocket back into the treasury as soon as the amount of the theft was determined. However, a special committee, appointed to look into the matter, questioned the Society’s moral obligation to reimburse him, for though the clerk was paid by the Society he had been hired by Hooper and worked under his direction. Angered and hurt by the committee’s attitude, Hooper, who had been Treasurer from 1893, resigned from the organization in a pique. Charges were not brought against Owen when his family agreed to make up the loss. The Hooper affair simmered on into 1911 and was finally brought to a conclusion when the Directors, with apparent second thoughts, decided to pay the former Treasurer $700 for “faithful services rendered.”

At its last dinner before the stability of the Victorian world was shattered by World War I, the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn joined in December 1913 with its sister society in Manhattan to celebrate Forefathers’ Day at the old Waldorf Astoria Hotel on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street. Ladies were still not admitted to these Manhattan affairs except as spectators in the gallery.

Benjamin Silliman lived to see the dawn of the new century and died on January 24, 1901, at his Brooklyn residence. On the opposite corner the flag on the Brooklyn Club, where he had been president for twenty years, flew at half-mast as four days later his funeral cortege moved from his house to the Church of the Pilgrims at Remsen and Henry Streets where final tribute was paid to this remarkable man who had known Burr, had been an associate of Daniel Webster, and a close friend of Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper. Now only one of the Society’s seven incorporators remained – Hiram W. Hunt, who died in 1902.

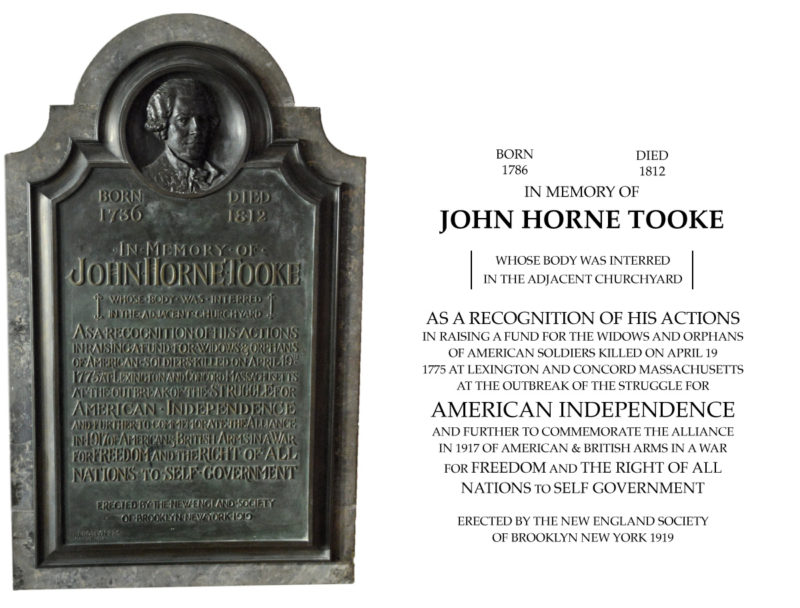

Part II – Transition

Naturally the Society’s activities were somewhat curtailed when the United States entered World War I in 1917, but less than a year after the armistice, in June 1919, it was once more demonstrating its obligation to recognize the worthy deeds of the past. In England American Consul General Robert P. Skinner, substituting for the American ambassador who had been called away to lunch with the king, unveiled a tablet given by the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn to honor John Holmes Tooker. The memorial was placed in St. Mary’s Church, Ealing, nine miles from central London where Tooker was buried. Though English, he raised a fund for the widows and orphans of the American soldiers killed on April 9, 1775, at Lexington and Concord. In addition the Society restored Tooker’s tomb in the adjoining churchyard. This restoration and the tablet not only recognized Tooker but also commemorated the 1917 alliance of American and British forces. At the dedication one hundred pounds was given by the Society to the British Orphans Fund for English children orphaned by the war.

Plaque erected by the New England Society at St. Mary’s Church in Ealing, London, England.

A. Middle Age

In December 1919 the Society held its Thirty-ninth Annual Festival and faced the 1920s and its “middle age” in a world at peace but greatly altered. Characteristically, it adapted its social occasions to contemporary taste and sought new realms of activity and expression.

Even before the war it was obvious that the traditional date of the Festival, coming as it did during the busy Christmas holiday season, was becoming inconvenient for a more mobile society and one presented with increasingly varied forms of entertainment. Preference slowly shifted to a November 21 date, that being the day on which the Mayflower reached Cape Harbor on Cape Cod as well as the day on which the Mayflower Compact was signed. The by-laws were amended to accommodate this change and to provide for flexibility, but by the mid-1920s, finding the November date often conflicted with fall football games, the Society decided to again honor the Pilgrim Fathers in December.

Emphasis in 1919-1920 focused on little else but ensuring an appropriate tercentenary celebration of the Pilgrims’ landing. Locally the Society observed the occasion at the Bossert with dinner, dancing, and a speech by Professor Stephen Leacock of McGill University. However, the Society was somewhat undecided what to contribute to the national celebration at Plymouth. Its sister Society in Manhattan had voted $50,000 toward the occasion, but the Brooklyn Society was less beneficent. When it learned that a contribution would be appreciated toward a “chime of bells” for First Church, to which the Society had given two stained glass windows eighteen years earlier, interest was aroused. The chimes, already in work at the Meneely Bell Company in Troy, New York, were to cost $14,000. The Society proposed to give $5,000 of this amount provided the full cost of the bells was raised in six months’ time. However, by March 1921 it was apparent that fundraising was not going well and, worried about its liability, the Brooklyn Society rescinded its appropriation and donated instead $2,600 for “a bell to be one of a set of chimes.”

THE HAMILTON CLUB. Organized in 1882, the Hamilton Club was an outgrowth of the Hamilton Literary Association of Brooklyn (1831) which included Benjamin D. Silliman and Alden J. Spooner among its members. It stood at the corner of Clinton and Remsen Streets. This view depicts the clubhouse, built in 1884 to designs by George B. Post, as it appeared in 1893 before the statue of Alexander Hamilton was placed by the entrance. The club, long a meeting place for New England Society Directors, was proud of its art gallery and library. A victim of the Great Depression, the building was razed in the mid-1930s.

In an effort to recruit new men to its ranks, which numbered about 240, and to revive the interest in the Society which existed before the consolidation of the city, the Directors at their meetings at the Hamilton Club in the mid-1920s spoke increasingly of the Society’s purposes. Out of these discussions came proposals to contribute funds for New England book collections at the Brooklyn Public Library and the Long Island Historical Society. But in 1926 a suggestion from Judge George Albert Wingate had far-reaching significance for the Society’s future. In March of that year Judge Wingate recommended that the Society pay the tuition of a deserving student at a New England college. Though not implemented in any way until 1929, when aid was given to Clarence G. Keefe, a blind student at Tufts, Judge Wingate’s proposition was indeed consequential.

Devoted to the New England Society, Judge Wingate, who became Surrogate of Kings County in 1919, was one of Brooklyn’s most distinguished civic leaders. In addition to his legal career, he had a military one as well which began in 1899. When he retired from the New York State National Guard in 1935, Judge Wingate had reached the rank of major general. Wingate & Cullen, the Brooklyn law firm established by his father in 1873 and with which he was also associated, still continues.

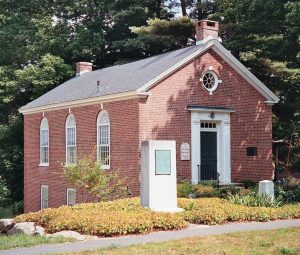

PETERSHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY BUILDING with “Shays Rebellion” stela and plaque erected by the New England Society and dedicated on July 4, 1927. The text of the plaque appears below.

ON SUNDAY MORNING, FEBRUARY FOURTH

1787

DANIEL SHAYS

AND ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY OF HIS FOLLOWERS

IN REBELLION AGAINST THE COMMONWEALTH

WERE SURPRISED AND ROUTED BY

GENERAL BENJAMIN LINCOLN

IN COMMAND OF THE ARMY OF MASSACHUSETTS

AFTER A NIGHT MARCH FROM HADLEY

OF THIRTY MILES THROUGH SNOW

AND COLD BELOW ZERO.

THIS VICTORY

FOR THE FORCES OF GOVERNMENT

INFLUENCED THE PHILADELPHIA CONVENTION

WHICH THREE MONTHS LATER

MET AND FORMED

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES

—

OBEDIENCE TO LAW IS TRUE LIBERTY

—

ERECTED BY THE NEW ENGLAND SOCIETY

OF BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

AS A GIFT TO

THE PETERSHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The Society turned its attention toward Petersham, Massachusetts, in 1926 and elected to erect there a monument commemorating the 1787 defeat of a group of insurgents led by Daniel Shays who rose up in western Massachusetts against the new American government. Spurred on by the depressed condition in the rural districts of New England following the Revolution, this uprising is popularly known as Shays’s Rebellion. On July 4, 1927, the memorial was presented to the Petersham Historical Society.

B. “. . . its original name”

In 1928 Dr. Edward E. Hicks, a member since 1914 and thus a relative newcomer, called the Board’s attention to the fact that the Society’s original charter of 1880 called for an existence of only fifty years, a span which was rapidly drawing to a close in the late 1920s. Dr. Hicks strongly recommended that a members’ meeting be called “to secure a perpetual renewal of the charter in its original name.” This action would then settle two issues, not the least of which was the Society’s official title. For years following the incorporation of Brooklyn in the City of Greater New York, the appropriateness of the Society’s original name had been debated without a satisfactory resolution. In view of the present renaissance of many of Brooklyn’s old neighborhoods and a renewed pride in being a resident of Brooklyn, Dr. Hicks’s endorsement of the initial name can be viewed as fortunate and prophetic. The action suggested by him was taken at a membership meeting held at No. 196 Montague Street on February 27, 1928, and filed in the office of the secretary of state the following month.

By the closing weeks of 1930 the effects of the Wall Street debacle in October of the previous year were painfully evident on Brooklyn’s wintry streets, and the Society’s Board, meeting as usual at the venerable old Hamilton Club, itself doomed by the Depression, appropriated $1,000 to meet the pressing needs of individuals recommended for assistance by members. Many resignations followed as economic conditions worsened in 1932 and 1933, but despite opposition the Annual Dinner continued. However, a smoker at the Brooklyn Club replaced the more elaborate spring reception which had been waning in popularity even before the Depression and was proving a financial loss.

Faced with the imminent closing of the Hamilton Club on Remsen Street, Judge Wingate, who had been elected President of the Society, proposed that the Directors move across the street to the Brooklyn Club and meet over dinner during the active season. The demise of the Hamilton Club, which the Brooklyn Eagle characterized in 1930 as the “ultra aristocrat of Brooklyn clubdom,” was a sad day in the annals of Brooklyn history. Of its ten presidents in 1882, over half were New England Society members. Its 1884 clubhouse officially closed in December 1934 following a merger with the nearby Crescent Athletic Club on Pierrepont Street (now St. Ann’s School), built in 1906 on the site of Benjamin Silliman’s residence.

Notwithstanding an occasional Directors’ dinner meeting at either the Hotel Margaret or the Crescent Athletic Club, the Society remained loyal to the Brooklyn Club throughout the 1930s, but for its Festival year after year returned to the Bossert, where a ten-piece orchestra could be engaged for an evening of dancing in 1934 for $60.

Still, membership was a problem. By 1935 the ranks had dwindled to 190 men. To find potential members, the Board canvassed the roster of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York and the list of Dartmouth College alumni living in Brooklyn. Mrs. Elizabeth S. Wells, widow of Walter Farrington Wells, boosted morale in those troubled Depression years when she established a fund to purchase a Society banner, a flag whose whereabouts are unknown at this writing. In 1953 it was reported in storage in the basement of the Brooklyn Savings Bank, one of Brooklyn’s great buildings, razed in 1964 while the Landmarks Preservation Law of New York City was still being drafted.

Early in the new year of 1937 the Society was notified of the death of Charles Harrison Otis, an event which was indeed a footnote to an era. Otis, who graduated from Harvard in 1873, joined the New England Society in February 1886 in the heyday of Silliman and Winslow, and had the distinction of holding the longest continual membership. But it was Marshall Wilfred Gleason, a founder of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, who held the record for longevity, dying in 1955 at the age of one hundred and one.

Part III – New Directions

Seymour W. Beardsley of Lloyd Harbor, Long Island, in 1938 re-established Judge Wingate’s concept of financial aid to students and suggested that the Committee on Charities take action in this area once more. In May, at a dinner meeting at the Hotel Margaret, a committee composed of Hunter Delatour, William H. Cary, and Edward W. Allen was appointed to develop plans for assistance to New England college students from Brooklyn. By fall Mr. Delatour reported that $500 would be awarded to William R. Wilcox, a 1938 graduate of Polytechnic Preparatory Country Day School for study at M.I.T. and the second recipient of a New England Society scholarship.

It was also at this autumn meeting in October 1938 that the membership rosette was officially adopted on the recommendation of a committee chaired by Frederick Starr Pendleton.

Though the founders’ vision of establishing a library became impractical and outdated, there continued to emerge periodically at Board meetings the suggestion that if not a library at least a collection of New England books should be started, the Long Island Historical Society being the preferred location. Judge Wingate was a champion of this scheme and had unsuccessfully advocated it in the mid-1930s. By 1941, however, attention had shifted to establishing such a collection at the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, then just completed on the Grand Army Plaza. Although the Society was told that the library could not accept a separate New England collection, it solicited gifts of specific New England related books which would be identified by appropriate bookplates. The plan was acceptable to a committee chaired by Judge Wingate, and in 1942 the Society appropriated money for a library fund. This was followed by other gifts in 1943 and 1944. However, in 1945 they were discontinued because of the committee’s displeasure over the lack of recognition afforded the Society. The funds used for books were then allocated to the Scholarship Committee.

A. Montauk

THE BROOKLYN CLUB. The Eagle and Brooklyn in 1893 characterized this, Brooklyn’s oldest social club, as “essentially a bachelor club” and more like New York clubs than similar Brooklyn institutions, which were often adjuncts to the home. John Winslow was one of its fourteen founders in the winter of 1864-1865, and Benjamin D. Silliman its president from 1870 to 1890. The club was located at the corner of Pierrepont and Clinton Streets in 1865, and in 1886 combined two existing structures into the brick and brownstone clubhouse pictured here. 1n 1915 it was pulled down for the new Brooklyn Trust Company building which now houses the Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company.

In the spring of 1940 the Annual Meeting was held at the Montauk Club in the Park Slope section, and several Directors’ dinner meetings ensued, recalling the days when Stewart L. Woodford, President in 1895, entertained the Society’s officers at his new house on nearby President Street. Though the Montauk’s Venetian Gothic clubhouse and its cuisine attracted the membership at large for its meetings in 1941 and 1942, the Directors returned to the familiar surroundings of the Brooklyn Club in the fall of 1940.

A year later, with the nation at war, the Directors voted to suspend the dues of all Society members in the armed forces of the United States during what was termed the “current emergency.” In addition the Society sent three times a year a carton of cigarettes to each of these men in uniform.

By March 1942 the Society added defense bonds to its portfolio, and at the Annual Meeting at the Montauk Club watched grim motion pictures of the London blitz. By June there was a serious depletion of members through deaths, resignations, and enlistments; and, when the Society’s activities commenced in the fall, the Directors decided to replace the Annual Festival Dinner in December with “some informal entertainment” at the Society’s expense at the Brooklyn Club. Though recipients were faced with imminent induction, the scholarship program was retained throughout the war years.

In the winter of 1944, over dinner at the Towers Hotel, the Directors decided to reinstitute the Annual Spring Dinner Meeting suspended during the dark, war-torn days of 1942 when it looked as if Rommel had the upper hand in North Africa. Thirty-one members attended the revived occasion and listened to an address by Colonel Edward C.O. Thomas, Director of Civilian Protection.

Two weeks after the German surrender in May 1945, and with the final land campaign of the war already underway at Okinawa, the New England Directors, gathered as usual about their Towers “roundtable,” discussed what form the Annual Dinner should take once hostilities ceased. August brought Japan’s surrender, and the Society’s members were soon thereafter solicited about resuming the customary “Old Time New England Society Dinner.” Their enthusiasm for bringing it back was boundless, and a date was set for a pre-Christmas affair on December 18. For old times’ sake the Bossert Ballroom was selected as the setting, and once again Society members and their guests ate and danced beneath its crystal chandeliers, dimly reflected in walls of Flemish silvered oak and Caen stone.

For some unrecorded reason the event was moved to the Towers the following December, an unwise choice perhaps, for in contrast to the festive exuberance of 1945, 1946 was a dead failure and had to be cancelled on a day’s notice because a mere thirty people were expected. Stuck with the bills for printing and for the orchestra, and somewhat crestfallen, the Directors dropped the December dinner from the Society’s calendar in 1947.

The late 1940s found Brooklyn once more in a state of metamorphosis following the disruptions of war. Robert Moses’ expressways made the suburbs evermore accessible, and young people were moving to the open spaces of Long Island and New Jersey. Brooklyn’s brownstones, now prized in the 1980s as they were a hundred years earlier, were then considered simply old-fashioned and inconvenient. With few exceptions the proud neighborhoods of the nineteenth century were receding into backwaters of the past. Prosperity and fashion had created them; obsolescence was to save them for a future generation of city dwellers.

B. Investments

In those years after World War II the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn began to lose its momentum. To maintain the status quo in the face of discouraging odds was, it seemed, all it could hope for. There was serious concern about the Society’s income, which no longer covered expenses, and it was decided that after the scholarship recipient of that time finished his studies the program should be suspended until the Society could build up its capital. After 1949 the allotment for scholarships, which had begun twenty years before, did not figure in the budget for three years.

For many years most of the Society’s assets were concentrated in mortgage investments, and in 1944 it held mortgages on four properties located in Sheepshead Bay, Canarsie, and Bay Ridge, most of which were proving increasingly unprofitable. Wisely, the Mortgage and Real Estate Committee advised the Board in October of that year to divest itself of its mortgage holdings, and moves were made toward that end. Further losses were sustained in the liquidation of the mortgages, but the minutes of the period reveal no regrets once a course of action was taken.

Under the wise stewardship of Christopher B. Fagan, Chairman of the Budget and Finance Committee and a Society member for only two years at that time, the New England Society’s capital grew, and in 1945 the Society made its initial venture into the Wall Street arena. With part of the proceeds realized from the sale of the mortgages, it purchased shares in Fidelity and Phoenix Fire Insurance Company, the Chemical Bank and Trust Company, and the Travelers Insurance Company. The remainder went into savings at two of Brooklyn’s venerable financial institutions: its oldest savings bank- the Brooklyn Savings Bank-and the East Brooklyn Savings Bank, whose second president was Darwin R. James, a Massachusetts native who joined the New England Society in the gaslit first year of its incorporation.

A man who played a significant role in sustaining the Society in the postwar era was Charles Lauriston Livingston, Jr., in whose honor a scholarship was named. He joined the Society as a young man in 1934 and was elected to the Board before World War II. Returning from military service, he joined the Board again in 1946 and resumed the office of Secretary. His detailed minutes proved invaluable in recounting the Society’s activities during the many years of his secretaryship. Descended from New England and Dutch stock, Livingston had a keen sense of noblesse oblige, a lifelong fidelity to Brooklyn, and followed in the footsteps of his father, on whose death in 1944 Conrad Saxe Keyes said, “His traditions were in keeping with his colonial ancestry.” In his tall brownstone house at 312 Garfield Place, crowded with family memorabilia, the Edwardian decade was remarkably prolonged and did not end until his death in 1974, a year after he stepped down from the presidency of the Society.

Though the Annual Festival had been abandoned in 1946, the Annual Business Dinner Meetings continued, with the Jade Room of the Towers Hotel the preferred location for these occasions. However, a filet mignon dinner at $5 with cocktails and entertainment provided by the Society usually attracted less that thirty-five people in the late 1940s. By 1947 membership had shrunk to a discouraging ninety-six, but a successful membership drive culminating in a dinner at the Montauk Club that spring brought in new faces.

Mid-century and a new decade brought some much needed rejuvenation. In 1950 the customary March Annual Business Dinner Meeting was postponed until July because of an invitation received from Branch Rickey, then in his last year as president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Mr. Rickey, who is perhaps best remembered for breaking the major leagues’ barrier against blacks, invited the New England Society members and their guests to a game at Ebbets Field on July 27. And out they went on a mild July afternoon to see the Dodgers defeated by the Cardinals and left in a mood which Harold Burr of the Brooklyn Eagle compared to that of “a bear with a smarting nose.” Following the game, the New Englanders repaired to the familiar rooms of the Brooklyn Club for a reception, dinner, and their belated Annual Meeting.

That autumn, still in a reanimated spirit, the Society drew seventy people to its New England Shore Dinner at the Towers and did as well the following year at the Montauk Club.

Even the truest Brooklynite cannot deny the magnetism of Manhattan. As Charles Lockwood points out in Bricks and Brownstones, Brooklyn in the nineteenth century “was tied, practically and emotionally, to New York across the East River.” Today this statement is still apt. Brooklyn residents have always been accustomed to working in Manhattan, but by the early 1950s many attractions which once kept them on their side of the river after dark, such places as the Bossert’s Marine Roof and Grill and the Academy of Music, had either closed or were in eclipse. Increasingly, people went to Manhattan for restaurants and entertainment. In a 1966 New York Times article entitled “In Brooklyn, Society Is by Invitation,” Charles L. Livingston told the writer, “There’s not much social activity in Brooklyn.”

It was not surprising that the Society crossed the East River in April of 1952 and held its Annual Business Dinner Meeting in the Bissell Room of historic Fraunces Tavern at Pearl and Broad Streets in lower Manhattan, owned by the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York whose membership roll included (and still does) several Brooklyn New Englanders. In December they assembled there again for a stag dinner and an address by Governor John Lodge of Connecticut.

C. Investing in Students

Under the presidency of Hollis K. Thayer in the early 1950s many of the Society’s gatherings were held at the Heights Casino, Brooklyn’s “Country Club in the City.” There, in 1952, the Scholarship Committee, under the chairmanship of Hunter L. Delatour, resumed its activities and committed $500 per annum to a student entering Williams College that year. The grant was increased as the Society’s portfolio reflected the convulsed economy of the 1950s, and in 1957 Nancy Clapp, the first female grantee, was awarded $1,000 for her studies at Wellesley. In 1957 the Society decided once more to hold its Annual Dinner in Manhattan. This time Whyte’s Restaurant, a famous old Fulton Street eating house, was selected as an appropriate location. With the drift toward New York in the 1950s, it came as no shock when Edward M. Fuller, First Vice-President of the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn and soon to be President of the New England Society in the City of New York, suggested at a Directors’ luncheon at the Brooklyn Club in October 1957 that the two societies merge.

Though they saw the advantages of such a merger, most of those present did not want to see the Brooklyn Society, in the words of Secretary Charles L. Livingston, Jr., “lose its distinctive character.” They moved that the matter be tabled and that notice be given when it was to come up for future discussion. However, Mr. Fuller was authorized to reserve a table at the New York Society’s Annual Dinner that year at the Plaza Hotel and to invite a group of Brooklyn New Englanders to attend the affair. In 1958 the Brooklyn Society was again at Whyte’s in the spring for its Business Meeting and with the New York Society at the Plaza in December.

Following the decision in 1959 to join once more the New York Society’s Plaza festivities, the Brooklyn patriots opposed to the appearance of a forthcoming union stated that the get-togethers were a tribute to Mr. Fuller (who by that time had become President of the New York Society) and not a permanent arrangement. They felt strongly that Brooklyn should hold its own dinners in the future, but New York won out again in 1960, 1961, and 1962. The beauty and elaboration of the New York parties were undeniable attractions, but another was the Brooklyn Society’s agreement to pay half the ticket cost of its members who attended.

At the Brooklyn Club on an April evening in 1963, Mr. Fuller once more pushed for a merger. Unquestionably, the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn was at a low ebb. Since 1960 membership had been below one hundred and had fallen to sixty-five in 1962, when for the first time in its eighty-two-year history no Annual Business Meeting had been called.

Among the adversaries to the proposed union of the two groups Everett M. Clark, a past President of the Brooklyn Society, and Dr. Stanley Hall stand out. The minutes of that April meeting reflect the strong sentiments of these two gentlemen and their fidelity to Brooklyn while this delicate matter was debated. Fully aware of the discouraging odds which the Society faced, it was Dr. Hall who finally roused the group to action and to the decision to continue as a separate entity as they had begun in 1880. On that spring night at the beginning of what was to be a tumultuous decade, the Directors pledged to rejuvenate the Society. Toward that end new rosettes were ordered and plans made for the Annual Business Meeting the following month. In May the Directors were heartened by a good turnout at the Brooklyn Club and, amidst an atmosphere of determination to survive and prosper, the scholarship fund was doubled to $2,100. Student aid was especially near and dear to the heart of Dr. Hall, and under his presidency (1964-1969) he emphasized it as the Society’s purpose and an attraction for new members.

But the specter of merger was not entirely dispelled. In November 1973 a small group from the Brooklyn Society met in Manhattan with members of the New York Society to explore again the possibility of a union of the two organizations or an affiliation between them. In the new year, they convened once more at the New York Society’s offices in the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society Building on East 58 Street, and there they drew up seven proposals concerning the recommended alliance. If approved by the Brooklyn Society, they would then be presented to the New Yorkers.

Five days later in the Governor’s Room of the Heights Casino, the Board of Directors of the Brooklyn Society agreed in principle to adopt the seven proposals and to take steps to implement them. However, little was done until the fall of 1974 when, in October, President Terry Lassoe called a meeting of the Directors at the Casino. There the recommendations were discussed at length and were ultimately withdrawn. At year’s end an ad hoc committee on the merger presented its own conclusions and recommendations and, based on these, the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn once more chose to pursue its course alone.

As he had been a decade earlier, Dr. Stanley Hall was the principal voice of opposition to the union of the societies in 1974. He insisted on strict adherence to the by-laws in all deliberations on the matter and strongly disapproved of the fact that the chief proponents were members of both the New York and Brooklyn Society Boards and therefore could vote in both camps.

During these deliberations over the Society’s future ongoing operations were maintained by the Secretary of the Board, Samuel Edson, and his successor, Frank Collin. Throughout this period George Warner Clark was Treasurer, and the work of the Scholarship Committee was conducted entirely by Henry W. Hotchkiss, who corresponded with students and met with them over lunch, invariably at his own expense. The work of these Directors enabled the Society to survive the difficult period prior to its resurgence in the mid-1970s.

It was during the presidency of Terry Ward Lassoe (1973-1977) that the tide turned and membership increased. Lassoe, in whose memory a scholarship is named, realized the importance of dedicated officers and committee chairmen who would work to rebuild the Society.

D. Bicentennial Celebration

On July 3, 1976, the Society celebrated the nation’s bicentennial with a cocktail party to which tickets were sold for the benefit of the scholarship fund. This very successful event was held in the observatory of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, Brooklyn’s skyscraper at Flatbush Avenue and Hanson Place, where an elaborate exhibition had been installed to commemorate the Battle of Long Island which took place in the surrounding area during August 1776. With a panoramic view of the city, members and their guests watched on that balmy summer evening as sailing ships assembled for the next day’s spectacular in New York Harbor. The harvest season dinner was revived on October 23, 1978, at the Gage and Tollner Restaurant on Fulton Street with a New England boiled dinner served in the upstairs dining room. Entertainment Committee chairman William Fisher concocted for the occasion a new New England drink, not with rum but with cranberry juice and vodka in more or less equal parts. He named it Brooklyn’s “cocktail” and exacted a pledge from the management that whenever New Englanders gathered there it would be available. The President of the United States was toasted and “America” was sung as always before, and well-received entertainment consisted of readings from the Society’s archives by several members. In fact, the evening marked not only the revival of the Annual Fall Dinner, but also the beginning of preparations to commemorate the Society’s first one hundred years.

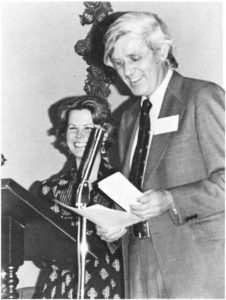

ONE HUNDREDTH ANNUAL MEETING. Entertainment Committee chairman Patrick Owen Burns introduces Dianne H. Pilgrim, Curator of Decorative Arts at the Brooklyn Museum. Ms. Pilgrim discussed the cultural period during which the Society was incorporated. (photograph by Stephen H. Parks)

The centennial was observed on March 18, 1980, when members gathered at the Brooklyn Club on Remsen Street. At this One Hundredth Annual Meeting plans for this publication were discussed, and it was announced that arrangements were being made for a return of those who had entertained at the Fall Dinner five months earlier. That evening had included both singing by the Whiffenpoofs of Yale and certain hilarity surrounding the dubious Socratic method used by Frank Collin to educate those present concerning New England.

If the Society began its second century with an enthusiastic and growing membership, it also had other thriving assets. The acumen of successive Finance Committees had, in the space of some forty years, resulted in a portfolio which by 1983 produced substantial aid to nine Brooklyn and Long Island men and women studying at seven New England colleges: Amherst, Brown, M.l.T., Northeastern, Wesleyan, Williams, and Yale.

To honor the Society’s scholarship recipients and their families and to mark the landing of the Pilgrims, an annual reception is held just before Christmas and as close as practicable to December 21. Thus, members still gather with guests at the time their predecessors joined together for the Annual Festival and, most fittingly, this reception is held in the handsome library of the Long Island Historical Society where New England Society archives are catalogued and maintained.

At the beginning of the Society’s second century most members live along the tree-lined streets of brick and brownstone row houses where the early members lived. Indeed, the rejuvenation of the Society and other organizations in Brooklyn parallels and, in part, is made possible by the renaissance of the residential neighborhoods surrounding the downtown area. Membership today includes men who follow in the footsteps of their New England predecessors and are leaders in their professions and trustees of the foremost hospitals, civic organizations, cultural institutions, religious organizations, colleges, and schools.